How Paris Made Me Come Alive on the Fourth of July

While America lit up fireworks, I found freedom in the land of my colonizers.

Contemplations:

What helps you stay embodied?

What helps you to look more deeply at yourself and the world?

How can you decolonize your worldview?

What does liberation feel like in your body?

When we arrived at the Orly airport last week, Jess and I had to take a shuttle bus to the main building once we deboarded our plane.

The heat superdome had followed us to Paris from New York City, where scorching temperatures hovered around 100 degrees Fahrenheit. I stood on the crowded bus, trying not to sweat through my white linen shirt that was covering my shoulders.

Two boys were sitting with their mom in front of me. At first, I thought they were a French family, arriving home—until I heard the mother speak and realized quickly that they had just flown in from Brooklyn. I heard the young mom, who could’ve been my age, speak to her two young sons in French and listened to both of them respond in English.

The older of the two was sitting next to the window. He looked about six and was quite adorable, explaining to his younger brother—who maybe was four—where they were.

“We were born here,” he said.

The younger brother furrowed his eyebrows and scratched his head underneath his baseball cap. He squirmed in between his mom and his older brother, looking out the window, and asked, “What does that mean?”

His older brother looked at him and pointed out the bus window, toward the center of Paris, and said:

“We came alive here.”

* * *

Last summer, Jess and I came to Paris for the first leg of our long-awaited honeymoon. Jess had been several times before, telling me that it was one of her favorite places in the world.

“I really hope you like it,” she said. “What if you don’t?”

I would shrug. To be honest, I’m not a fan of well-traveled cities, as I generally prefer going to remote locations that make me feel like wherever I am is my little secret. I also had conflicting feelings about Paris.

I thought: How would I feel about going to a country that had colonized my people for more than 65 years? But my parents assured me that I would love it — if not for the food alone.

I thought: Well, I knew that the French people were kind and funny, as I spent most of my high school years hanging out at my best friend’s house who was French. I didn’t really know or care about words like colonization back then, we were just two teenage girls trying to figure out life in Texas together in our immigrant homes. But we laughed a lot at her house, ate a lot of cheese, and I never really felt a care in the world when I was there.

“I think you’re gonna love it,” Jess would say after a few moments of silence from me, breaking up my train of thought.

She was right. I did love it.

There is much to love about Paris. It is a vibrant city pulsing with art, culture, and setting the highest culinary standard of food in the world. It is beautiful—and prides itself on holding the title of being the most beautiful city in the world, after Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann transformed the city under the orders of Napoleon III to clean it up, to put Paris back on the map after years of political upheaval, deep poverty, and disease.

To much controversy, to bring Napoleon III’s vision to life, Haussmann destroyed historical neighborhoods — often with autocratic methods by imploring eminent domain and forcing the displacement of poor, working-class folks even further to the margins of the city.

His urban development plans meant widening and straightening the boulevards that linked central landmarks and creating a sort of “central path” through the historical axis of the city—from the Louvre, Place de la Concorde, Champs-Élysées to Arc de Triomphe. This wasn’t just to connect and centralize the city but also to prevent those same poor, working-class people from building barricades to prevent future uprisings or revolutions — something that Napoleon witnessed and hated.

So that iconic look that Paris is now known for — the white-washed stone buildings with the black iron gates, often with cascading red roses draping down its balconies —was built on, what many historians would argue, authoritarian power.

It was this same imperial vision that pushed Napoleon III to declare himself the Emperor of the Second French Empire and what made drove him colonize my ancestral homeland of Vietnam — one that has had irreparable repercussions on the Vietnamese people for more than a century, as our own form of toxic nationalism was born out of the desire for freedom: a civil war, known to Americans as the Vietnam War and as the American War to the Vietnamese, that would force my parents to flee and seek political asylum in the States.

* * *

Simply being in Paris is a practice of mindfulness of the body.

Us Americans love to be disembodied from everyday life — whether that’s being buried in our phone or working ourselves into the ground. The oppressive nature of the American capitalist dream loves to keep us as disconnected from our bodies as much as possible.

Our country has proven over and over again that it prefers profits over own humanity.

So it’s hard not to fall in love with the city of love (La Ville de l’Amour) — and not just because our last visit was our honeymoon (though that helped). Paris is a sensory-filled city: from hearing its beautiful language to its foods and smells. Working is a thing here but not the thing, you know? And walking through the Tuileries Gardens, dancing under the glowing moon across from the Eiffel Tower, drinking more natural orange wine than I knew existed — all of that helps me be more in my body, to be more present.

Mindfulness of the body is everything in many ways. There is a reason why it is the first foundation of mindfulness. It is our invitation to the present moment, helping ground us our monkey mind; it is the gateway for us to witness what is happening internally; it is the access point to our humanity. (A short practice can be found here in the Plum Village app and a dharma talk from Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh on the practice here.)

This, to me, is what Paris invites me to do — even in all its complex history with its own country and my ancestral homeland. It is why I love it and why we decided to go back again.

I’m sure Paris is not perfect and there are many ways that colonial systems are still ingrained in this city that a tourist can’t see in a few days but even still, Paris embodies so much of what I search for in my daily mindfulness practice and why I love it so much:

Paris centers love, beauty, and presence.

Paris invites you to have reverence and respect for process.

Paris simply wants you to stop and enjoy life, to be.

To me, this is radical.

To me, this is anti-capitalism.

To me, this is the practice.

This is how mindfulness can be culture; culture can be mindfulness.

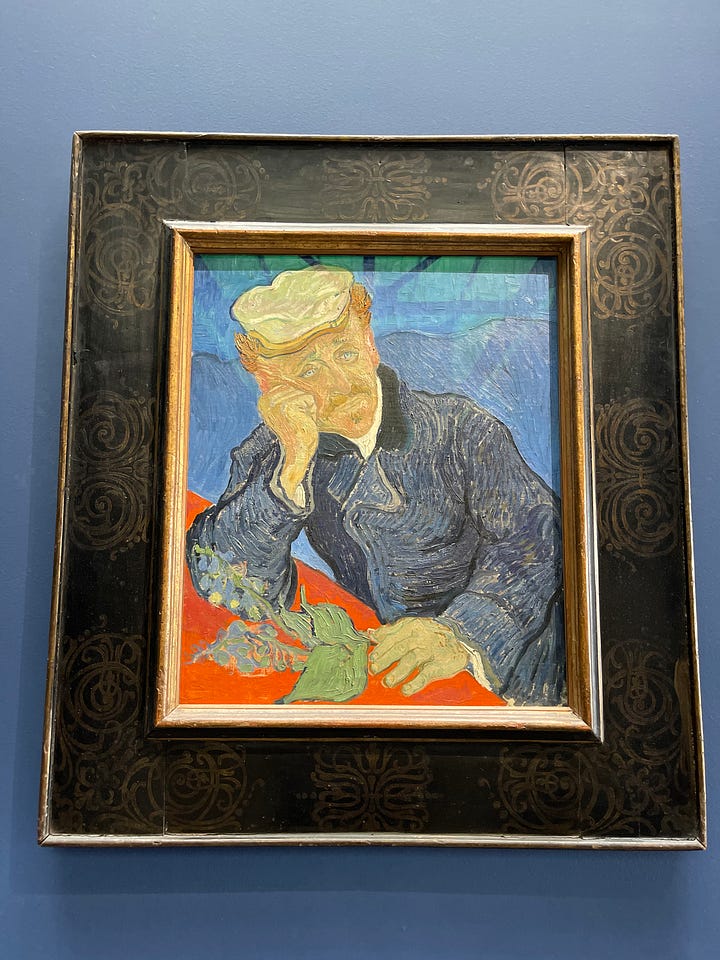

Last year, I was able to tap into a practice of looking deeply through being in the present moment. My heart stopped and lit up when seeing the movement in Rodin’s sculptures or Van Gogh’s suffering in his brushstrokes. The art didn’t just help me notice and see the world around me, it woke me up.

This year, we skipped over many of the touristy stops and stayed in the 11th arrondissement (11e) — what ChatGPT told me was the Bushwick of Paris.

As we walked around 11e, I was struck and heartened by how many people of color were in the area. We had stayed more centrally last year, close to all the tourist attractions, and I was constantly searching for a single person of color, wondering where they were and how they were.

But here, on the quiet street of our Airbnb, I saw everyday life: Algerian men laughing on the streets, Tunisian chefs selling street food, Muslim women walking their kids to school, Palestinian and trans flags flying from balconies across the neighborhood and Pho 11, Pho 27, Pho 33, and Pho 56.

I learned later that the 11e was where many activists came together, before and after the “Haussmannization.” That this neighborhood was the heart of the revolutionary spirit of Paris — and continues to pulse as a hub for immigrants, activists, and radicals who all embody Liberté, Égalité, and Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity).

The neighborhood was a good reminder that the people are not its government — or its history. My best friend and her family showed me that all those years ago and as we walked through the streets of 11e, I saw how you can water the seeds of goodness in a culture and leave the oppressive parts.

This is my practice of decolonizing.

I knew that more than anyone in that moment, watching America pretend to be the land of the free across the world by celebrating July 4th with hot dogs and planning future UFC fights.

As fireworks shot off in the States, I couldn’t help but notice that I felt more connected to the idea and possibility of freedom in Paris than I have in America for years. Watching authoritarianism destroy our democratic systems — as this administration illegally deports immigrants, further diminishes the needs of the most marginalized with a “big beautiful bill,” and all the loud and quiet Supreme Court decisions that are demolishing our civil rights — does not spark inspiration.

All of it is so ironic: that the day that represented “American freedom” felt more oppressive than ever. As I stared at Marianne, France’s Lady Liberty, towering over me in the Place de la République, I thought it was even more ironic that the very revolutionary spirit Napoleon III hated and wanted to suppress was alive and well almost 175 years later because of his own decree of making the city beautiful — that it was that very beauty that helped me be present enough to touch a sense of freedom, that I felt it more in that moment in the land of my colonizers than the country that provided a refuge for my family.

As I gazed at beautiful Marianne, I wondered how the French people found the courage to start their revolution. I wondered what was the final straw. I wondered how many people died for freedom — for themselves, for future generations, for people to remember that freedom is everyone's birthright.

The practice reminds me that regardless of what is happening externally in our government and our systems, through mindfulness, I can always feel liberation in my body.

It is powerful and easeful;

Strong and gentle;

Joyful;

And safe.

It is my heart beating out of my chest,

Tears streaming down my face;

Laughing,

Dancing.

Bursting

With light

Amidst the darkness.

It is realizing

I am alive

In this body

Right here

Right now.

It’s realizing no one can take that away from me, as hard as they try.

So as we make our way back to the States, I am deeply grateful for all the things that Paris has taught me: this practice of presence — of looking deeply enough to see the beauty in things, of mindfulness of body, of the feeling of liberation.

Just like those two kids, Paris made me come alive.

Now the work is to keep on living.

For me, for us, for freedom.

* * *

Practice

Contemplations:

What helps you stay embodied?

What helps you to look more deeply at yourself and the world?

How can you decolonize your worldview?

What does liberation feel like in your body?

Thank you for this journey through your eyes. And The Thinker. Meaningful. ❤️

So good to be reminded the US is not the center of it all. So good to be reminded resistance includes nourishing ourselves with experiences that keep our hearts open to learn from others. Thank you Kim!