How Buddhist teachings showed up in Oscar movies this year

These best picture noms explore equanimity, karma, the bardo and more!

I’m a pop culture junkie. I always have been and I always will be. And perhaps the only thing I think about more than pop culture is Buddhism.

Often, when I am watching something, I can’t help but see the Buddhist teachings underneath the surface of the movie, whether intended or not. So in honor of the Oscars this coming weekend, here are the themes I saw this awards season.

Some disclaimers: I haven’t watched all the best picture nominees — that’s 10 movies, folks! So I’d love to know what you thought of the ones I haven’t gotten to yet. Also, slight spoilers ahead.

‘Barbie’ as Buddha

I wrote about this last year when the summer blockbuster came out. A reader even confirmed after my piece was published that apparently director Greta Gerwig compared Stereotypical Barbie’s journey to Siddhartha Gautama’s when explaining the movie’s concept to Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling. Many more teachings here — including exploring Buddhanature and attachment of self.

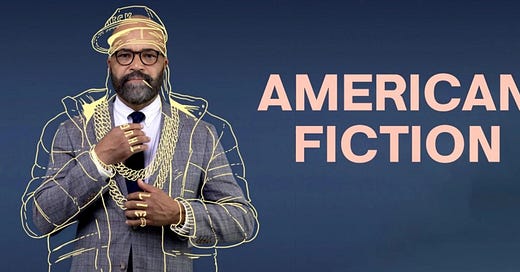

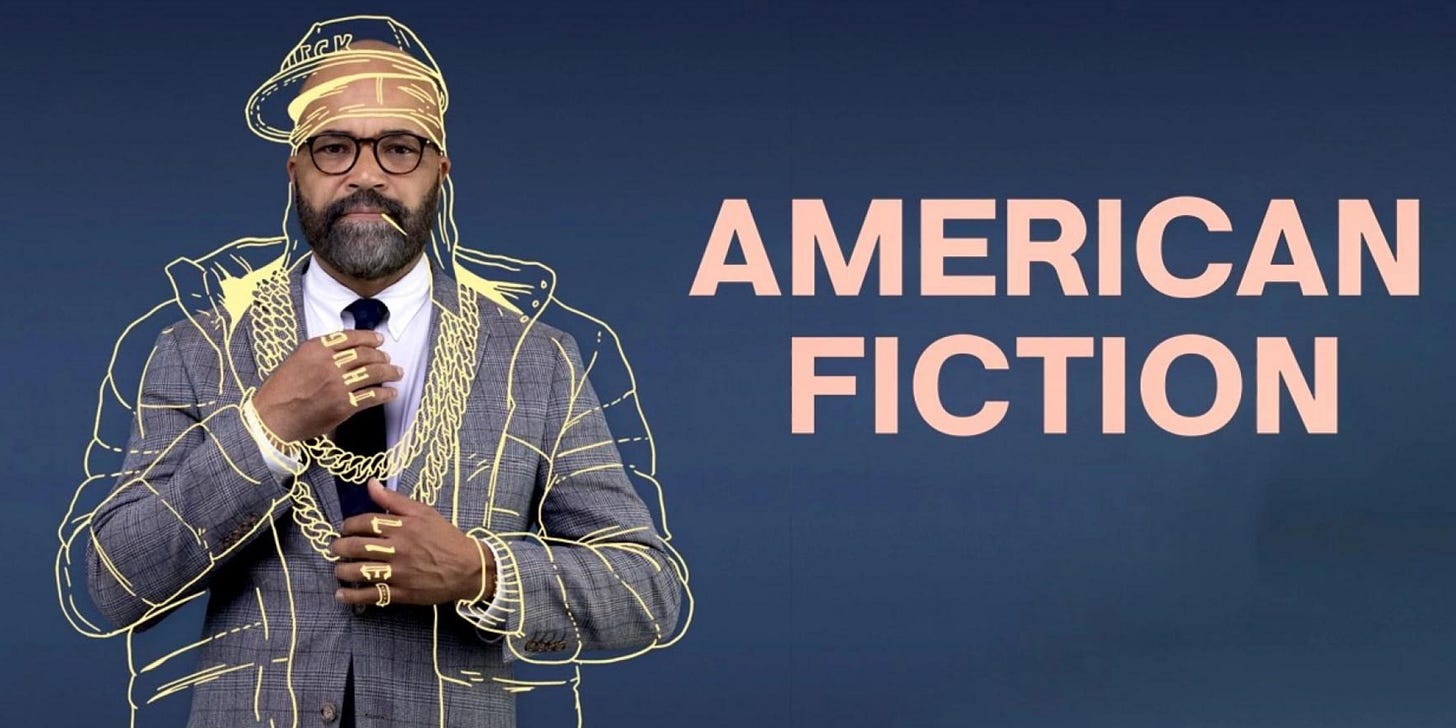

‘American Fiction’ is a provocative invitation to cultivate equanimity

Let me first say that American Fiction might be one of the smartest films I’ve seen in my life. It is incredibly layered, nuanced and does so in such a ambiguous way while still knowing exactly who they’re talking to and what its message is. Based on Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, American Fiction is the feature writing debut of Cord Jefferson and stars Jeffrey Wright, Sterling K. Brown, Issa Rae, Erika Alexander and Tracee Ellis Ross.

The film follows “Monk” (Jeffrey Wright), a frustrated author who can’t seem to get any of his publishers to move on his books because they aren’t “Black” enough. So as a big fuck-you, act of protest and joke, Monk writes a book that falls into the confines of how white people want to hear about the Black experience. The kicker is that it’s a huge success.

The film’s dark humor explores the nuances of identity and race with such grace, irony and heartbreak that it leaves you a bit speechless. It’s an incredible invitation for the audience to think not just about how we view the Black and African-American experience but how inhumanely we consume and exploit the pain behind those experiences.

The paradox of identity is that it often leads to the simplification, flattening of the self, which then leads to “othering” and by effect, separates us and creates much suffering. Brother Troi Bao Tang talks about how on some level our perspective will always be obscured if we minimize the way we see someone from one vantage point:

“…none of us we have the same shape. But yet in our mind, we create a some kind of identity category…and then question, am I enough?

I practice as if everything has ultimate and historical. Historically at the moment, I'm a monk. But ultimately, I'm not only that. I am also a son of my parents. I am also a brother of my siblings at home. I am also a friend. I'm also many as many things as possible, and everything.”

This provocation, this mirror in American Fiction is the perfect invitation for us to continue looking deeply at not just identity politics but why identity even exists to begin with — and how we can start moving towards a world where we know there is more to a person than one particular story or stereotype.

In the same way, Brother Bao Tang invites us to look at the wholeness of who we are, American Fiction invites us all to cultivate a greater sense of equanimity — the practice of holding all the things. That means seeing that the Black experience is not just comprised of one thing but understanding that extends far and beyond what we will ever be able to define. And the brilliance of American Fiction is that it does that and so much more.

‘The Holdovers’ dwell in the bardo

The bardo is a concept of the liminal space between death and rebirth in Buddhism. In many different forms of the teachings, it’s argued that any period of “in-between”, of “transition”, is essentially the bardo. (Check out Ann Tashi Slater’s great series on the bardo for more.)

The bardo can be a scary place; it can also be essentially the present moment — and so one of the many teachings here is to see how we can dwell in this space and not let fear take over. In many ways, the bardo is another way to teach how we can be present and dwell in the present moment.

The Holdovers (directed by Alexander Payne) takes place at a boarding school over winter break where the three main characters are left to themselves because of a series of unfortunate events — death, abandonment, retribution. It is over this time period, we see the characters — a crass and curmudgeonly teacher (Paul Giamatti), a troubled student (first-timer Dominic Sessa) and the school cook (the incredible Da'Vine Joy Randolph) face the real reason why they are there. It is through the bardo, we see them explore the roots of their suffering, grieve for their own personal losses and emerge on the other side with a bit more peace and resolution.

It is their time in the bardo that made that all possible. The movie uses this time period as a smart container to not just tell the story of these characters but essentially is a character in the story itself in the same way that New York City is a character in Sex and the City (first version only, please). This winter break — or the bardo — is essential to first “create” the suffering, then makes them look at their suffering, and ultimately transforming it.

‘Past Lives’ is a heartbreaking look at karma

I have so many things to say about Past Lives. It’s an incredibly beautiful meditation on identity, love, and the paths we choose. The beautifully exquisite film directed by Celine Song follows Nora (Greta Lee) and Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), two childhood friends who fall in and out of love with each other across the world. We feel the push and pull of Nora’s choices to not only stay in America but to love and marry a white American man, making her contemplate and think about what her life would have been like if she had stayed in Korea and instead had married Hae Sung.

The film is spacious, quiet, intimate and portrays the conflicts we feel in the aftermath of our choices. Often we think about karma as a punitive term, but in the Buddhist canon, I think of it really as a matter of physics, of action and reactions. As physician Jan Chozen Bays says, “Because if you understand karma, you really understand who and what you are, and you understand the rest of the universe too, because the laws of karma are universally applicable.”

This is what we see in Nora, who through this relationship, reflects on the entirety of her life, how different it could have been if she had made different choices. We see her quiet aching grief, her heartbreaking contemplation of whether she could have been happier than she is now — and her reach to touch the parts of her Korean self that have faded into the background over time as she has settled into a life in America.

Karma is the foundational idea behind rebirth and reincarnation, that our past actions continue to ricochet into our next life. And though Nora is still in this body, we see that clearly in her new life in America. The constant tension in the movie is whether she will continue on the path she is on or decide to start a new journey, a new forging, a redirecting of her karma. Past Lives explores this with such gentle grace, as we are invited to question the idea if we are the victims or the creators of our own circumstances — and if there is such a thing as “too late”?

Anatomy of a Fall explores the construct of truth

Anatomy of a Fall is a gripping crime mystery thriller that leaves you questioning what is truth. The movie opens up immediately into the scene of the crime when Samuel (Samuel Theis) dies.

The rest of the film, partly spoken in English and French, looks at whether his death was a murder or a suicide. Director Justine Triet does an incredible job of leading the viewer to believe one thing and then completely undermines it. The film’s strength is its ambiguity and Hüller’s incredible stoic, often cold performance leaves you intentionally questioning whether or not she killed her husband.

We eventually slowly start moving into the perspective of Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner), their half-blind son who is torn apart by the confusion he feels: Did his mother kills his father? Did his father kill himself? What is worse? What is true?

Daniel agonizes over the details, what he thought he saw that day, what he misremembers. Another character in the story tells him that the reality is that he might not ever know the truth and that he ultimately must decide what happened.

And by extension, Triet is then asking the viewer to decide as well. This intentional ambiguity is the brilliance behind this film. We, the viewer, just like Daniel have to sit with the obstructed view of reality.

This is so Buddhist is so many ways I can’t even take it! A core teaching is on attachment, or upādāna, and the practice in many ways is constantly letting go of your thoughts, and essentially the concepts of your mind. It is one of the two root causes of suffering and so much of what we practice is about working with that grasping, that clinging. By letting go of what you think you know, we then by default will recognize that not everything we think we know is true, and that truth is essentially what we perceive it to be. This deeper understanding that the world around us is created by our own meaning and perceptions of reality is essentially the great teaching on emptiness.

Truth, to put simply, is a construct, and is all relative, bab-by! If you don’t believe me, then watch Anatomy of a Fall and see the half-truths for yourself.

***

So tell me what themes/teachings you saw in these movies and the other Oscar noms. I’d still love to watch the rest of the ‘Best Picture’ selects and also want to hear about any films (always) that didn’t get the spotlight it deserved.