Creating your own Land of Happiness

“The temple may be ancient but the meaning is always modern.” — an ancient Bhutanese saying

This is from the Kim Thai Archive. It is an original travel essay on Bhutan from 2019. To access more from the Kim Thai Archive, become a paid subscriber.

I first heard about Bhutan a few years ago when its King (yes, King) announced a new system of measurement for the country — Gross National Happiness (GNH).

“(GNH) is based on the conviction that material wealth alone does not bring happiness or ensure the wellbeing of its people, and that economic growth and ‘modernisation’ should not be at the expense of the people’s quality of life,” writes Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck, Queen Mother of Bhutan in The Bhutanese Guide to Happiness.

What a bold and wild concept for this American.

After discovering GNH, I quickly went down a Bhutanese rabbit hole. I found out through my Googling that Buddhist values are deeply infused and ingrained in its culture and widely practiced but not mandated among its citizens. Not to mention, it is landlocked between India, China and Tibet, fairly untouched and tucked away in the Eastern Himalayas, and is referred to “The Last Shangri La” by many tourism companies in the West.

I distinctly remember putting Bhutan to the top of my travel bucket list that night, as I became fascinated by how this small country seemed to live such a drastically different life than the rest of the world.

I’ve talked incessantly about Bhutan to my close friends since, fantasizing about a remote life where I would own and run a goat farm in the Himalayas, being the Millennial hipster that I am. (Spoiler: This is not actually possible. Yes, I looked into it. There aren’t really goats in Bhutan. The closest animal is its national animal, the takin — a beautifully, majestic nearly-extinct type of Himalayan bull that produces no milk!)

So once I heard that my yoga studio was hosting an advanced Bhakti yoga training program in India, I looked to see how far Bhutan would be. I could be in Thimpu, Bhutan’s capital, in about three hours from Delhi. And I knew in that instance, that it was time for my #yolopilgrimage.

I was so curious — was Bhutan really just great at selling itself or would I be able to see a world that would inspire me to shift my entire perspective?

As I boarded Druk airlines, I was curious to see how far the reality would be from my fantasies.

Arriving in the Land of Happiness

The minute we landed and the flight attendant opened up the door to our plane, I knew I was definitely in a different world. I stepped out of the plane and the Himalayas greeted me, as I descended down the stairs to the tarmac. The airport itself was designed in what I know now is a special type of architecture developed in Bhutan over the years that mixed East and Southeast Asian cultures with its own Buddhist aesthetic.

As I started exploring the Western part of Bhutan with my tour guide, the reality of what Bhutan was far exceeded what I had hoped — in fact, it felt like I was in a dream state most of the time I was there. I had wanted to see a world that was driven by the values of lovingkindness and compassion and it definitely was — living, breathing and thriving in the Land of Happiness with “No Hurry No Worry” signs on the road; the universal mantra for compassion (Om Mani Padme Hum) painted everywhere; monasteries on every corner.

Astounded, I sat back to see if this was just all pomp and circumstance, did the innerworkings of Bhutan match its window dressing?

The short answer is yes. I observed more times than I count when natives would go out of their way to help one another, almost every sales person would either crack a joke or hug me in appreciation, and meditation was as much of a staple of life here as eating.

Everyone’s default mode was: general ease and contentment — something that became acutely obvious to me when my tour guide, Nima, constantly told me to relax. Funny part was that I thought was.

Someone equated this ease to island vibes to me recently, but it was different. There’s an acute awareness from everyone, an attentiveness that I’m normally used to seeing. The difference is that it was filled with, dare I say, compassion here, not just regular ‘ol anxiety.

What still amazes me is that everyone seemed to know about Buddha’s life, the eight-fold path, the middle way, and centuries of monastic history. The tenants of Buddhism seemed to be common knowledge here — in the way that I had to learn about the Battle of the Alamo, growing up in Texas.

We’re all romantics, aren’t we?

Two encounters jump out at me. The first was when I walked across the bridge in Punakha, a more rural town in central Bhutan, and saw a group of women pounding water out of mud with tall wooden sticks to create the roof of a house. I watched them joyously sing while they built this roof, waving at me from afar. I asked Nima why they were singing — he said that they view this kind of work as a way of building community and they sing because they believe that hard work should also be fun. He asked me if it was like that in America and I stared blankly at him, mind blown.

“Not exactly,” I said.

The second encounter was with an art store owner. He told me about his philosophy behind the art he curated and created — that it was all for the intention of invoking peace for his viewer and hopefully the world.

I was speechless, looking at this endearing, older Bhutanese man, deeply feeling his intentions. Suddenly Celine Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” started playing on his little boombox.

“Good song,” I said, breaking the silence.

“Yes, it makes me cry. I love Titanic,” he said as his eyes watered.

It was impossible not to charmed by his sincerity.

I smiled and said, “you’re quite the romantic!”

“Oh we all are!” he said adamantly. “Don’t you want to love and to be loved?”

“Of course.”

“Then, don’t just classify me!” he said with an uproarious laugh.

We both laughed. He hugged me goodbye and thanked me for visiting his shop and I walked out, letting go of bits and pieces of my cynicism that we Americans have.

Knowing who you are

I spent the rest of the week, quickly acclimating myself into the gentle rhythms of Bhutan.

As we drove up and around and down the blue Himilayan mountains through the western and central parts of this beautiful country, I started realizing how much thought was put into different aspects of its modernization. Despite being in the rural countryside, I had cell phone service the entire time, access to WIFI and almost everywhere I went, every shop owner accepted credit cards. Toilets were clean, and everyone seemed to be fully up to date on world news and yet almost everyone dressed in traditional garb, lived in village homes, went through painstaking efforts to create artistic creations by hand, and almost never had dessert with their meals. (Wild, I know.)

One thing was for sure: There is a deep knowing within Bhutan’s people of who they are. A feat that I feel has been challenging for me as a first generation American. #identity

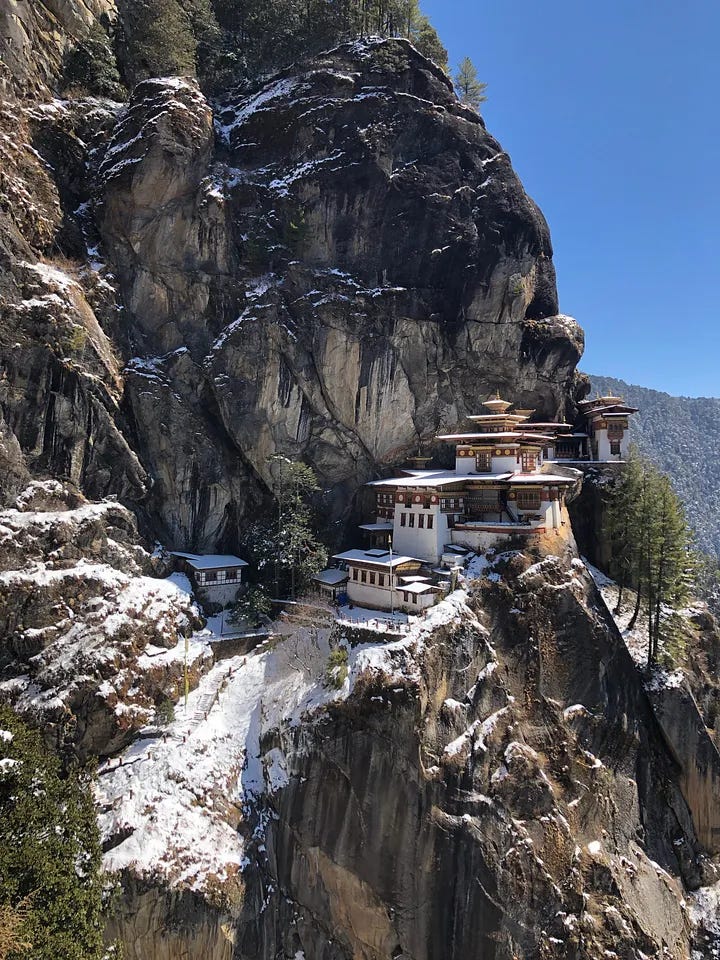

As I walked towards Tiger’s Nest Monastery, a majestic temple that is somehow built on the steep vertical cliffs on the side of a Himalayan mountain, my tour guide showed me a particular plant that hung from the blue pine trees that lined the hiking trail, telling me that it only grew in environments without pollution.

He showed me with such a sense of pride. Actually everything he did was filled with a sense of pride— even the stories he told that he knew might be received with a sense of skepticism — like how Tiger’s Nest was found.

Legend has it that Guru Rinpoche, who is hailed as the second Buddha by many, transformed his wife into a flying tigress and rode till they found this cave where he meditated for three years, three months, three weeks, three days and three hours to help fight off the evil spirits that were plaguing Bhutan.

Nima told me this story with such enthusiasm that I, too, accepted it as historical fact, choosing to believe in the magic of it all rather than questioning it. I was after all in a country that valued its people’s happiness over how much they made and seeing a reality that I wish could be my own.

Balancing the modern world with tradition

Nima knew what they had was incredibly special, saying how grateful he was that he got to live this life in Bhutan — a country that somehow had struck a graceful balance between preserving and protecting its land, cultural traditions, mystical history with the forces of modernization.

It has left me quite in awe of what is possible — and how to live my own life. I took a step back and remembered how lucky we were as Americans to have everything at our disposal, something my mother, a war refugee, still says with a amazement.

As I looked out at the Bhutanese fields, I asked myself if in fact I needed everything I had access to and wondered if there were ways in which I could do my own filtering, my own curation to create a more balanced life for myself.

There’s an old Bhutanese saying that says “The temple may be ancient but the meaning is always modern.”

As I heard the daily prayers done twice a day — once in the morning and once at night, a ritual that has been instilled since the 1600s — I deeply saw, heard and felt how that holds true.

So yes, we can do it for the ‘gram all we want, but can we be inspired by Bhutan’s bold intentions of doing it all for the intention of something greater? Can we all learn something from this special place in the world that has upheld the ideas of lovingkindness and compassion through centuries of modern development — that no matter the time and place, we can recognize that a devotion to these ideas will hold up the test of time?

Now that I am back home — in my lovely, oh so different New York City — I have been deeply inspired by this idea that we can absolutely live a life dedicated to these bold notions.

And more than anything, I will forever remember that it is possible in this very complicated world we live in to create our very own Land of Happiness, not just in the far reaches of Bhutan, but where ever we might be.

Kim- I like your keen observation on the monastic 'awareness' as opposed to island vibe. What stood out to me in the monastic lifestyle is really the willingness to do the monotonous, even to the point of boredom (which is a word that exists only because of lack of better depiction). This willingness I think is one of the things that really bring that acute awareness. In monotony, the mind and being has no other option but to focus on things outside, underneath, inside, and beyond said monotony. It really is quite beautiful.